The more disruptive the level of a technological innovation, the more diverse (and to some extent unpredictable) the scope and degree of its future potential implementations.

This consideration holds certainly true for NFTs:

Their distinguishing feature relies on the “unique” nature of the resource, whereas standard “fungible” digital commodities (just as currencies) are, and ought to be, ontologically interchangeable.

“Non-fungibility” ensures the specific identification of a single tokenized asset, thus making NFTs perfectly suitable to univocally represent on the blockchain environment a set of utilities that may autonomously exist (as discrete exploitable and exchangeable goods) in the off-chain world.

That said, although the technology supporting NFTs may be indifferently applied to intangible or physical resources, the basic rationale inspiring the tokenization process cannot completely remain unaffected by the nature of its reference asset.

The rise of digital arts

In light of the above, it should not come as a surprise that digital arts is the sector that has crucially contributed to raise the public awareness on this topic, increasingly attracting the curiosity even of a non-sophisticated audience.

VISA buying a Cryptopunk for $150k is just the peak of a huge iceberg, represented by a massive amount of daily transactions regularly concluded in heterogeneous fields such as that of the gaming, entertainment, sport or audiovisual industry.

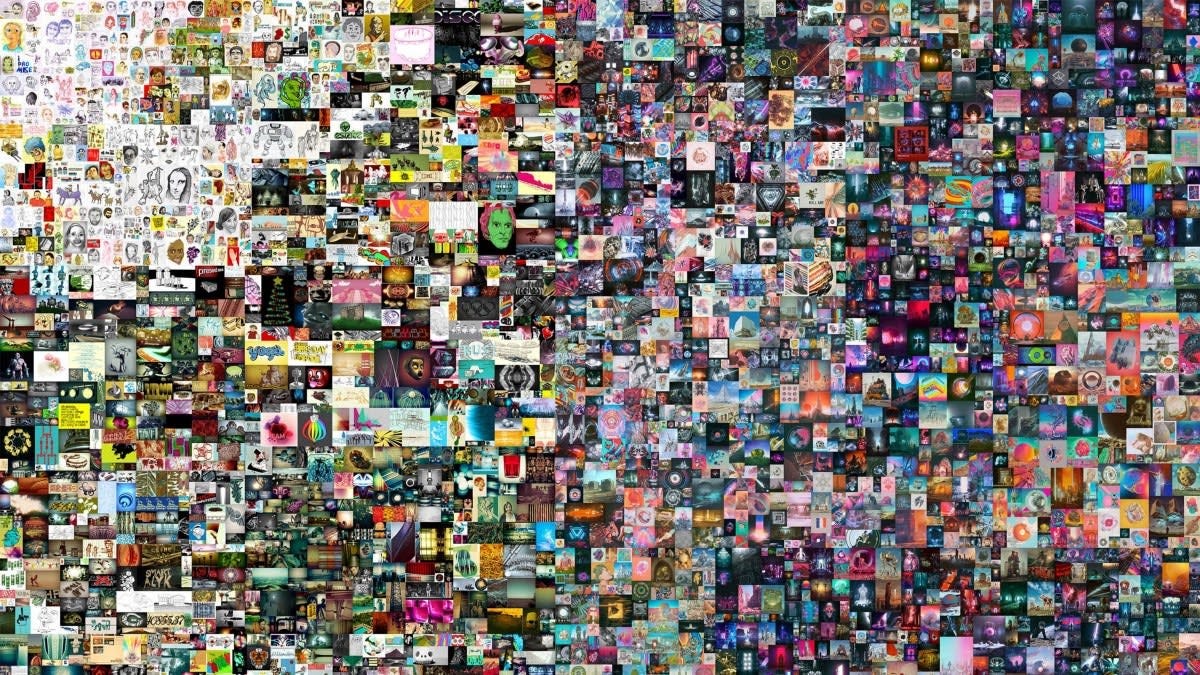

And also fine arts are included! As seen with the widespread coverage granted by the generalist media to Christies’ auction of Beeple’s masterpiece “Everydays: The First 5000 Days”.

In all these contexts, the blockchain technology serves, among many others, one apical goal: that of artificially turning multimedia products in a unique (non-fungible) asset, with a pedigree of originality that would not have been equally achievable in the ordinary digital environment. This eventually fosters the level of demand and the consequent emergence of new market sectors, raising the excludability for resources that otherwise could have been infinitely shared or copied at zero costs without depleting their consumption value.

NFTs as property: from virtual real estate…

With this in mind, one might at first cast serious doubts on the rationality of analogous tokenization processes when applied to land and immovables, which represent the ideal type of scarce tangible resources, rival in consumption and easily excludable precisely in the light of their physical dimension.

Consistently, a relevant part of the debate on “real estate NTFs” refers to virtual environments, commonly known as metaverses. In this context, NFTs embodies a certificate of ownership of a unique file representing a refined 3D ecosystem projected by visual artists like Krista Kim, author of the Mars House, the first digital ambient sold in 2020 through a Sotheby’s auction.

Following the basic pattern, virtual land and immovables can be traded and sold as NFTs on platforms like Decentraland or Cryptovoxels, where metaverses can be sorted and chosen according to their characteristics, not differently from what happens in real market contexts (where, e.g., a plot of buildable land in a commercial unban area has a higher market quotation compared to merely agricultural fields in a peripheric rural zone).

The main purpose of these transactions is clearly that of investing, but owning and administering NFTs digital properties express also a use-value for those engaged in “living” a virtual reality, looking at metaverses as way to socialize similar to the experience granted by platforms like Second Life in early 2000s.

… to “real” real estate

All this, however, should not lead to disregarding the relevance of the issue when it comes to “real” land law. The news of the first attempt by Propy to sell a Ukrainian apartment as an NFT has recently attracted media attention, and it leads to the investigation of the benefits of the blockchain technology applied to property management and to its legal implications and technicalities.

The main parallelism that easily comes to mind to anyone who has ventured into a basic real estate transaction is that, as with the records in a DLTs, also tangible immovable goods are administered as registered properties. Although with technical differences around the legal systems of the world, every prospective buyer, interested in acquiring rights on a plot of land, an apartment, a factory premise, has to invest time and resources in the scrutiny of a register to solve a fundamental question: who owns what on that good?

Today, official land registers are centralized and administered by public authorities, even in those advanced systems that have already promoted their digitalization. This means that property transactions cannot be directly concluded among the sole interested parties, and that governmental servants, regulatory authorities, public officials (like notaries) are necessary intermediaries in every property deal. On the one hand, this system grants reliability and certainty in the real estate market; on the other, it certainly raises the costs of negotiations, lowering in particular the level of possible transnational property transactions, and consequently investments in real estate on a worldwide scale.

In this context, the blockchain technology looks as a valid, more effective and efficient, solution: with the single property turned into a NFT, the DLT may work as a decentralized, immutable record of ownership, capable of representing a secure database, ensuring immediate evidence of the chain of titles while enabling direct private transactions among interested parties. Moreover, the possibility to provide tokens with metadata ensures a more detailed tailoring of the underlying assets, which can be transposed on the blockchain system originally wrapped-up with a clear set of additional features and information related to the power of use, possess and dispose granted to the owner or to the holder of lesser property rights over the immovables.

Designed in this way, the digital public register represents a reliable record apt to constantly granting full traceability of the token’s title together with an immediate understanding and enforcement (e.g. through the execution of smart contracts) of the rights and liabilities deriving from the legal regime of the goods that back-up the NFTs. At this point, regulatory interventions and policy adjustments seem needed to turn evolving strategies into consolidated real estate practices.

One first move has been made in Wyoming's Teton County, where an immutable archive of land records on blockchain, which can be viewed through a web portal, has been established. Another experiment has affected Vernacular Land Markets, i.e. informal markets through which land is allocated outside of statutory regulations. It is questionable whether these projects will bring to a wider adoption of the technology. At any rate, the high risk of hackings should be carefully evaluated before promoting the abandonment of the old-fashioned land registers.

In the meanwhile…

As always happens, the industry tries to anticipate regulators.

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations, as CityDAO and RealDAO, specialized in real estate are growing and offer innovative licences connected to NFTs. The scheme is simple: A DAO acquires ownership and manages the rights on the land through its governance framework and NFTs.

On Opensea it is possible to acquire an ERC-721 NFT with an incorporated legal agreement representing the grant of an irrevocable license to allow RealDAO members to use a portion of land shown on a site plan for the sole purpose of traversing the real property on foot. It is also provided that the licensor may not camp on the real property nor place a van by the river. In addition, the token includes a cryptographic hash function in order to map the executed document using IPFS.

Although referring to licenses, the example shows some further advantages of blockchain technology, which enables users to rapidly assess significant information (e.g. the number of transactions/sales records) and grants huge web visibility through decentralized applications. All this could lead to a significant increase in the value of tokenized real estate.

Nevertheless, the question is still open on how to harmonize such initiatives with the role of the governments and official powers, and how to frame titles and rights resulting from the blockchain systems with the standardized series of entries generally allowed by official public registers. Moreover, when NFTs attribute rights to enjoy real estate to a multitude of individuals, some features of blockchain technology get lost.

Relationships between people (and possible conflicts) would occur off-chain, in the “real” world.

—Musicman is a Property Law expert interested in the legal implications of the digital revolution

—eaglelex is a Law Professor interested in DAOs, NFTs and DeFi (twitter @EaglelexE)